The Scrawl congratulates author Eloise Williams on being the first Children's Laureate for Wales as she takes up the new ambassadorial post which aims to engage and inspire the children of Wales through literature.

Eloise Williams was born in Cardiff and grew up in Llantrisant and is proud of her Welsh working-class roots. She graduated with a BA (Hons) in Drama from the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, then a Postgraduate Diploma in Acting from Guildford School of Acting.

After spending a decade working as an actress she found her writing muse and took up the pen, pursuing her MA in Creative and Media Writing, which she completed with Distinction at Swansea University. Her performance and writing skills make the perfect combination when working with children in schools and libraries.

Her second novel, Gaslight, was awarded Young People’s Book of the Year 2017 by the Wales Arts Review. This year, her latest book, Seaglass, has been shortlisted for the Welsh Book Council's Tir na nOg Awards and the North East Book Awards...

|

| Eloise Williams, author and Children's Laureate Wales |

Eloise Williams talked with Remy Dean for The Scrawl about creativity, education and environment... about reading and writing books, and helping children to love words and find a voice to tell their own stories...

The Children's Laureate for Wales is a new honour and involves a two-year commitment... So, as the inaugural Laureate, here is a question you are going to be asked often: what does the Children’s Laureate do?

It’s a good question! I think it’s open to interpretation. I’m going to talk to young people about my love of reading, encourage them to read for pleasure themselves and also get them writing their own stories.

There’s definitely room for more authors in Wales and I want future generations to be enthusiastic about telling their stories in their own voices. I think there’s a bright future for literature in Wales if we can get young people involved.

I’m working with too many children who do not own a single book. We need to be fighting to get more books into schools. There are only 67% of schools in Wales with a designated library space. What message are we giving to young people with this?

Many children don’t know that they can access books for free from a library or that they can request a book. I’m trying to put this right – where libraries are still available. We need to campaign to keep our libraries open, especially in areas of deprivation.

I also believe there’s a real connection between a child meeting an author in ‘real life’ and them wanting to read. I’m hoping that my visits to schools and libraries will encourage them to build connections with other authors once my laureateship is over.

It is a very exciting time in education for Wales. I have been involved with a few projects now, as a Creative Agent and Practitioner for the Arts Council of Wales on their Creative Learning Through the Arts Initiative - sorry for that huge label - and this model is now being recognised globally as a new paradigm. I wonder what you think of the new Curriculum for Wales, which prioritises creative thinking, and if you feel it is relevant to what you will be doing?

Absolutely. I’ve been working as a Creative Practitioner for Arts Council Wales on their Creative Learning through the Arts initiative for the past three years too! I think creative thinking and learning is the way forward. I’ve seen pupils engage in a wide range of subjects which have been taught through the arts in a way which their teachers assure me they haven’t before.

My laureateship is also an opportunity to promote creative thinking. Reading for pleasure is in itself an important part of my message and has, of course, immeasurable benefits on wellbeing, self-knowledge, empathy and literacy. I also want young people to understand that what they are reading will make their imaginations grow in a way which will help them to think more creatively. I truly believe that education isn’t about what you know – it’s about how you think about what you know.

I think the Arts Council initiative really gets young people involved in their own learning and that’s an important element of what I want to convey too.

|

| Gaslight (2017) was the second novel by Eloise Williams |

What are your own best and worst memories of school?

I have lots of good memories of primary school and not many at all of secondary! I was (and still am) such a shy person. It is difficult to survive in a place where you are expected to stand up in front of groups of people and join in with group discussions consistently.

I think there’s even more of a sway towards forcing young people to be extrovert today than there was then, and I am gently reminding people that ‘quiet’ doesn’t mean ‘not engaged’ as I go along.

Luckily, I find it lots easier to talk in front of people now than I did when I was younger, but for me it came at a later age and I still have days where nerves get the better of me.

Ironically, the best part of secondary school for me was my drama lessons and performances where I got to hide behind someone else’s words by playing a character. I also enjoyed studying Shakespeare in English. Thankfully, the teachers wisely went for Macbeth and Othello so there was lots of blood, treachery, murder and witchcraft, which kept it interesting for us!

Not really a question, but an observation about the remit to keep every pupil in a class engaged at all times... If I had gone through school with a teacher trying to engage me every second, it would have been hell!

I think some children need time to wander among their own thoughts and I learnt more that way than when I was actively ‘doing’ in class. This is especially the case, I think, when trying to engender ‘creativity’ within children. This may be the difference between being an intro and extro -vert. This is something the David Lynch Foundation has taken on, with pushing schools to introduce quiet meditation space into the timetable... and one good thing about reading is, with a book in front of you, you can look engaged whilst thinking your own thoughts, too!

Agreed! This is also true of when a teacher is reading aloud to the class, I think. Time to let your thoughts wander. If I wasn’t a daydreamer, I wouldn’t be a writer. I spent lots of my school time looking out of the window and imagining.

One thing about creativity, I find, is that one mode benefits from another – I write and paint and walk, as well as writing creatively, I write critically about film and media… do you do any other art or creative thing that feeds into your writing?

Not at the moment! I don’t have time! I do walk a lot and that gives me lots of new ideas and creative energy. I also sing around the house and often accidentally out loud when I’m walking. My husband is an artist so you can sometimes find oil-paintings drying in the oven – I do intend to have a splodge one day.

…and whilst on creativity and writing, some say that long-hand involves different parts and processes in the brain, so, which do you favour and if you do use both long-hand and keyboard, at what stages to they dominate?

I start with long-hand. I make notes, maps, character outlines, write down interesting themes or words which I’d like to include in a story. When I have a fair idea of the world I’m trying to create. I switch to using a laptop. I can type more quickly than I can write, and my thoughts come in really quickly so it’s a more effective way to keep up. My stories take a lot of editing after I’ve completed a first draft and I’ll often go back to my handwritten notes to help me with that.

What age group do you think of as your typical readers, and what were you reading at their age?

I don’t think of an age group as my typical readers. Children’s books are for everyone!

When I was younger, I read lots of different authors. C.S. Lewis, Enid Blyton, Judy Blume, Tolkien to start with and then I quickly moved from there to Stephen King and Shirley Conran in my early teens. It was quite a leap.

So, how do you deal with publishers and booksellers asking what grade or age-group a book is for?

I let the publisher deal with that. I didn’t even know what middle-grade meant when I started writing. I just wrote.

Now I try not to think about it. My main protagonist is usually around the 11-13 age and that’s where I place my stories, in that protagonist’s world. If that means the story is middle-grade then great. It doesn’t stop my Nan reading it, and she's 94.

What is your earliest memory of reading a book that really drew you in and transported you into its world?

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is undoubtedly the book which had the biggest effect on me as a child. The idea that there could be another world through a portal as ordinary as a wardrobe completely blew my mind. It had an effect on me which has lasted for about forty years.

My husband recently pointed out to me that every holiday I want to go on consists of large forests and snowy landscapes. There’s a reason for that.

Can you tell us about a few of your favourite writers and what you have learned from them?

There are so many writers who are favourites and have influenced me.

Everything I’ve read has taught me something. Maya Angelou taught me to be honest. Stephen King’s book On Writing taught me to get on with it.

The children’s writers who have influenced me are too long to list I’m delighted to say. Hundreds of them.

Becoming the first Children’s Laureate for Wales is quite an accolade and I should think feels like quite a responsibility! How has this new commitment affected your attitude to writing and your follow-up books for children?

It is a wonderful and brilliant thing. I am thrilled to have been selected and yes, it does feel like a responsibility. However, I’m not letting it change the way I write, or the stories I tell.

I’m always influenced by the young people I work with so that might have an effect on future stories, but I’m not consciously going to change anything at all.

I think there’s a real danger with writing to follow the trend but by the time you get there the trend will have moved on. I’m going to carry on writing the stories which speak to me and ask me to tell them.

Has talking directly to young people sparked a story for you?

Yes, but I’m not telling you what it is because it’s in the long-hand note stage and I don’t want to kill the spark!

Can you recall when you first 'woke-up' to being a writer?

I didn’t really give it much thought until I was in my thirties. I’ve always worked creatively and had been an actor and theatre practitioner for more than a decade, but it wasn’t until I was feeling stunted creatively and looking for a new outlet that I thought about writing.

I enrolled on the MA in Creative and Media Writing at Swansea University to give it a go and eventually graduated with Distinction. It wasn’t an easy time and I received a warning at one point to tell me I was in danger of being asked to leave the course because I was missing too many workshops – I had to work to find the money to fund my studies and live at the same time – but it was worth it in the end.

It gave me some of the confidence to believe I could make a go of it. The confidence is still a rollercoaster. Highs and lows all over the place. I lose it weekly!

I’ve noticed a lot of MA assignments specify they must ‘not be written for children’. What was the attitude to those writing for children on the MA course?

Writing for children wasn’t covered by the MA course at that time. I don’t know if it is now. I didn’t start writing for children until I’d finished the course, so I have no training as such in how to do it, I simply wanted a challenge.

There wasn’t an attitude towards people writing for children as nobody - as far as I know - was doing it. There is though, I think generally, an attitude that writing for children is somehow easier. I often getting people telling me how they’d like to write a ‘nice little book’ like I have. I wish them luck! I think it’s much harder to write for children than for adults for many reasons.

Do you have a writing ritual or regimen?

No. I wish I did because it might make me more reliable.

If I’m working at home, I get up and write. Then I go to bed. That’s it!

I’ve tried rituals to make me feel more like a writer. They don’t. They just help with procrastination.

Is there a favourite tipple or treat when writing?

Tea to the point of heart palpitations. Then water.

If you have a usual space where you write, can you describe what you can see from there?

I write wherever I am, but I do have a writing room with a view of a Lebanon cedar tree and a sea glimpse.

It’s a messy space and I share it with my dog, Watson Jones. He can see the occasional squirrel passing by which always causes chaos and eventual earache.

Your website shows pictures of you and Watson enjoying the local sea shores and landscape of Pembrokeshire, how do you think environment affects how you write or what you write about?

I am hugely inspired by my surroundings. For some of my books I’ve used them specifically. In Seaglass, for example, I walked the local area a lot before starting on the story and made lists of all the details using my senses to bring the landscape to life. The landscape really is almost a character in that story.

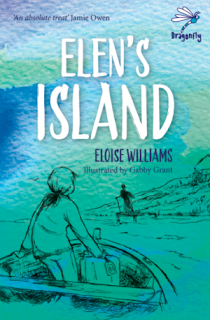

For Elen’s Island, I stayed on Caldey Island for three nights to get a good feel for the place and also visited Skomer several times.

Gaslight was slightly different because it’s set in the Victorian era, but I spent lots of time living in Cardiff, so I know it well and revisited many of the places I included in the story.

My next book is in an imaginary Welsh valley so that was a different experience again. Still heavily inspired by place though. It includes the Sgwyd yr Eira waterfall and takes its names and inspiration from the South Wales Valleys.

How do you decide and settle into the story to write next, do you have too many ideas crowding your creativity, or is it a matter of waiting and listening carefully to the muse?

Thankfully, I have lots of ideas for stories. Perhaps too many. Settling on a specific story is so much more difficult than coming up with ideas for me.

Do you consult your editors, or your muse, to decide a priority?

When I first started writing I just let the muse decide but now I ask my agent. She gives me a good indication of whether she thinks the story has ‘legs’. Having said that, if I felt passionately enough about a story, I’d write it anyway.

What, if any, do you think are the duties or responsibilities of a writer, in general, and one that writes for children and young adults, in particular?

Write the best story you can, as creatively and truthfully as you can. That’s the key, I think. If you are working with an editor and a publisher, they will let you know if you’ve gone wrong.

I think there’s a definite danger of writing in a patronising way when creating stories for children. My advice on that is don't!

What next from Eloise Williams that we should be looking out for?

Wilde comes out with Firefly Press in May 2020. It’s about a girl who is afraid of being who she truly is. Wilde is desperate to be normal and fit in at her new school. But in the middle of a fierce heatwave, when a school play wakes up the old, local legends of a witch called Winter. When ‘The Witch’ starts leaving other pupils frightening messages, can Wilde find the truth and break the curse? Or will she always be the outcast? All she knows is that being different can be dangerous!

Thank you, Eloise Williams, our Children's Laureate!

for news and updates, see the official Eloise Williams website

or follow her on twitter

books by Eloise Williams are published in Wales by Firefly

for more information about the Children's Laureate Wales, click the logo below

or follow her on twitter

books by Eloise Williams are published in Wales by Firefly

for more information about the Children's Laureate Wales, click the logo below