Conor O’Clery is a respected journalist who worked for the Irish Times for thirty years and was twice awarded Irish Journalist of the Year. He reported on the 9/11 attacks in New York which he witnessed from three blocks away. He is the author of a dozen books, some tackling complex aspects of political history.

He was a resident correspondent in Moscow for the last four years of the Soviet Union and has written a book centred around the very last day of the Soviet Union, Moscow December 25 1991. He married into a Russian-Armenian family and to write his latest book, The Shoemaker and His Daughter, he draws upon the personal history of his wife and her family as a unique perspective on 80 years of Russian History since Stalin, through the administrations of Kruschev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev to perestroika and Putin.

|

| Conor O'Clery (author photograph courtesy Transworld) |

He talks to Kim Vertue for The Scrawl, about his process, and his writing life...

Who have been your favourite authors and what have you learned from them?

In general, Grimms’ Fairy Tales, Voltaire, Graham Green, Hubert Butler – an Irish essayist of mid-20th century. I learned from the Grimm brothers a love of the forests and mysteries of European imagination, from Voltaire insights in the human condition, from Graham Greene the power of story-telling and from Butler the beauty of an elegantly-written essay on politics and conflict.

What motivates you as a writer?

I am basically a story-teller. I like telling people news and bringing news or historical events to life with anecdotes, detail and historical background, and bringing people to life with deft use of dialogue.

The type of books you write must demand a bit of a juggling act between research skills and writing in an accessible way. Do you have a preferred writing approach, ritual or regimen? Do you interview, transcribe, write long-hand, or is it all straight into a PC?

For this book I transcribed all interviews longhand into an interview book. Separately, I compiled a chronology. I also created a bulky file of downloads from the Internet. Moreover, I acquired about seventy-five books for background information, including books on social and political life in the Soviet Union, biographies of Soviet leaders, histories of the Russian, Chechen and Armenian peoples, a work on trial law in the USSR, and, believe it or not, I unearthed a book on the life of the Soviet Automobile, called Comrade Cars.

Did the desire to write The Shoemaker and His Daughter arise as a result of extensive family history research, or was it conceived as a way to tackle the story of Russia since Stalin, from the outset?

The idea came from Brian Langan, then of Transworld, who, along with his colleague Eoin McHugh, pitched it to me over coffee in 2016. They knew the outlines of the story from what I had written in my preface to Moscow, December 25, 1991, The Last Day of the Soviet Union (European edition published by Transworld). The concept was developed through family research and was envisaged from the start as a social history of the Soviet Union and Russia told through the experiences of Zhanna's family, and it became of course a comprehensive family memoir.

I visited Krasnoyarsk and spoke extensively to family members, especially Marietta [Zhanna's mother]. I called Marietta regularly. For other descriptive material I visited Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia and Romania, and I had already extensive experience of the old Soviet Union through living there for more than four years and visiting Grozny and Nagorno-Karabakh in the course of my reporting. Of course, I had my own experiences upon which to draw as a member of the family for the last 26 years and an occasional visitor to their home and dacha.

How did you balance this – with the hindsight of the historian, and as an eye-witness to the latter events in particular?

I compiled a family memoir first. Then I researched and expanded and enriched the telling by adding and interweaving the social and historical landscape into the text.

The great humanity of your father and mother in-law shines through, their personal integrity and family loyalty offers a beacon through the upheaval of recent history. One is also struck by how they embraced their new Siberian home, the taiga, and its austere beauty. The description of a meal shared at their dacha is particularly evocative. One has a sense of timeless things, like a feast shared and family events celebrated, are the constants that can overcome so much suffering. Is your wife and her family pleased at your portrait of their history?

Yes, they are. Marietta was rather touched to have her family's story told, but I detected concern at the start about resurrecting the family secret - Stanislav's imprisonment [Stanislav Suvorov, the shoemaker and Zhanna's father]. She was relieved that my research established the injustice of his imprisonment. Indeed, the book rehabilitates Stanislav. Zhanna found it painful to recall some events, particularly pertaining to her husband Viktor's death, but she was committed - once the decision to go ahead with the book was made - that it should be a full and honest account.

|

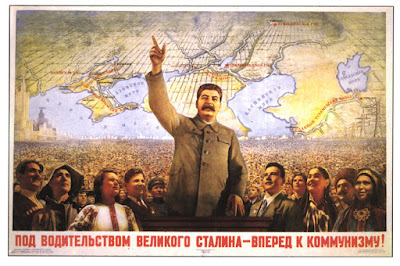

| Propaganda poster from the era of Stalin |

Will it be translated into Russia and made available there?

Not yet known. I hope so.

The personal hardship of so many Russians, and the story of the Armenians and Chechens in particular, are made vivid by this story. It seems the forced movement of peoples within Russia was one way Stalin sought to dilute national identities, yet these are still an important factor in understanding modern Russia. Currently Brexit is underway here in the UK following some baffling political decisions, while Lithuania Latvia and Estonia all embrace their EC membership. Clearly, there is still much focus of National borders and integrity within the melting pots of Europe, Asia, America. After writing this book do you have any opinions on how this may reach resolution so that ultimately more global concerns, such as climate change and food production, can be addressed in a way to help the future of humans and the world in general?

If the UK had a large and aggressive neighbour, as have Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, there would be no question of separating from a protective entity like the EU or NATO. Conversely, a Christian country like Armenia has to look to Russia for last-course protection because of its isolation in an unfriendly Moslem world.

Did you recognize any parallels between the history of Russia and that of Ireland?

Both countries had for centuries a peasantry ruled by a small elite, and had revolutions at roughly the same time, but Ireland opted for the democratic structures inherited from Britain, rather than communism. There are some striking social similarities between the two. People in both countries know their poets. Also both have a fondness for alcohol, story-telling and anecdotes.

What Irish tradition or attitude do you feel you have exported to Russia?

I’ll assume that the 'you' in your question refers to Ireland. Well, there are Irish bars in every Russian city - several in Krasnoyarsk - which have conveyed a rather faux Irish drinking tradition and there are St. Patrick's Day parades in Petersburg and Moscow…

What is your favourite, essentially Russian, food that you may crave?

Pancakes with caviar.

What is the most positive thing you have learned from your research and knowledge of political history?

I learned that sometimes, in the words of a centuries-old Irish ballad, The Man from God Knows Where, that "the wrong does cease and the right does prevail". These words ran through my head when I was reporting on the successful efforts of the suppressed East Timorese to end a cruel Indonesian occupation.

In general, the most positive thing I have learned is the resilience and the basic decency of the vast majority of people in the world.

Finally, what ‘in-a-nut-shell’ could you offer young journalists or historians beginning their careers?

Get out of the office.

Meet people rather than communicate by telephone.

Go to events, rather than monitoring news on other media.

Never assume anything- it is one of the great sins of journalism.

If reporting abroad pay people the basic courtesy of trying to speak their language.

Never miss a deadline.

Most of all make your writing interesting - detail and colour are everything.

Thank you, Conor O’Clery.

Conor O’Clery was talking with KimVertue

is published 23 August 2018 (hardback) by Doubleday Ireland.

|

| The Shoemaker and His Daughter by Conor O'Clery |

This is the story of an ordinary family who bear witness to extraordinary times as the slow demise of communism and the chaotic embrace of capitalism batters and shapes their lives. A powerful tale of this secretive world, spanning more than eighty years of Soviet and Russian history. Husband to the shoemaker’s daughter, Zhanna, Conor provides a beautiful insight into the hardships of life during this time, the compelling tale of some exceptional women, and the remarkable relationships of the Suvorov family.

No comments:

Post a Comment